Bhavan's Campus, P.B No.8

0495-2443222

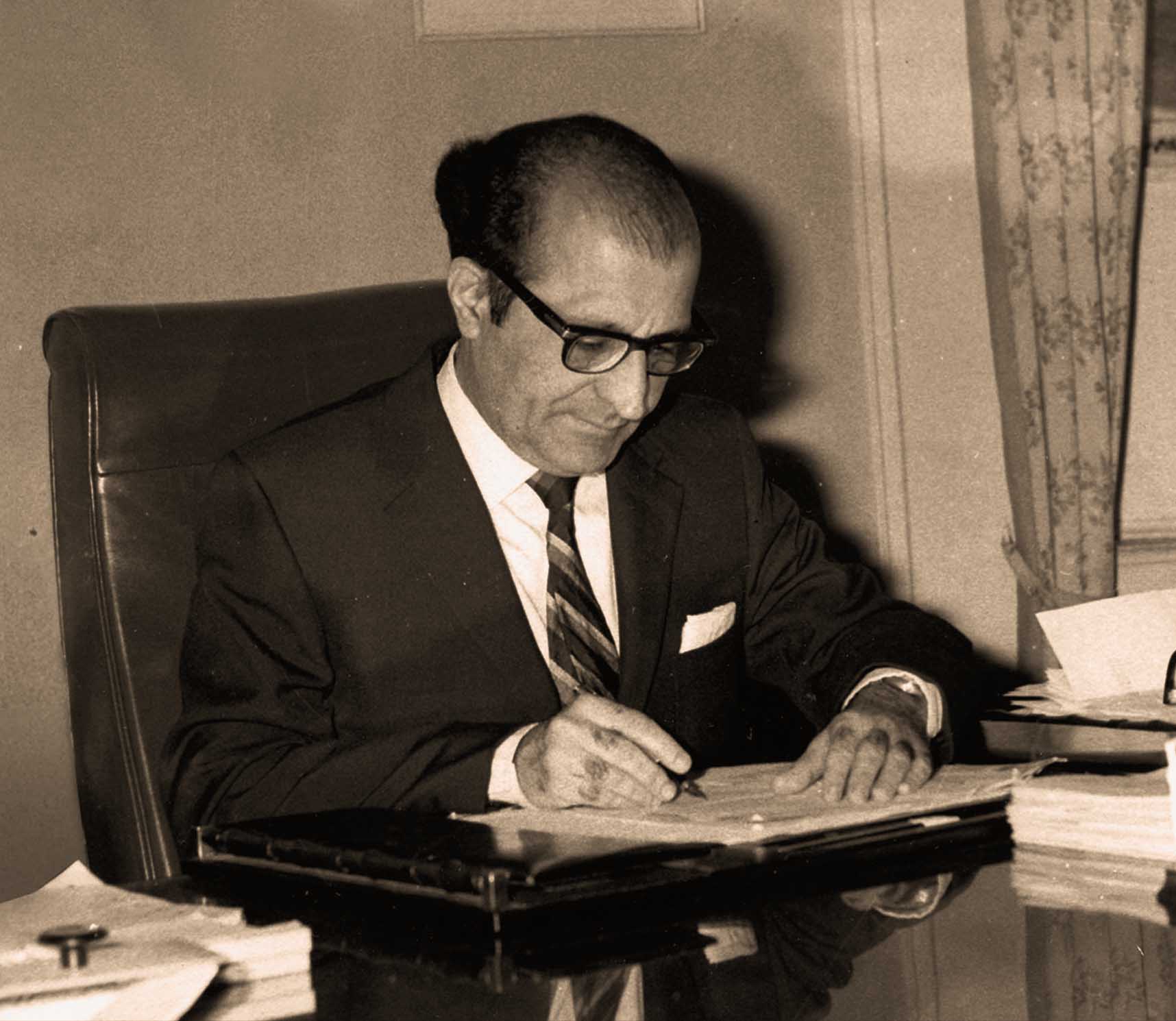

Ardeshir Palkhivala (Nanabhoy) was born on 16th January 1920 to the blue collar middle class Parsi parents in Mumbai. The parental pair was so rare and great that Palkhivala said about them: “To my parents, to their love and care and guidance, I owe a debt which could never be repaid. From them I learnt that all the loveliness in the world can be reduced to its first syllable. My father inculcated in me a passion for literature, which has remained an abiding joy throughout my life…. My mother was a woman of exceptionally strong character who could meet with Triumph and Disaster and treat the two imposters just the same….” That was a family where love ruled. From them Nani and his siblings learnt lessons which no school, no college, no university could impart. The children studied in school but educated at home. The father and mother inculcated great values in the children.

Nani, even as a schoolboy, never wasted time. Forgoing food and other necessities, he would save money to buy secondhand books. Pleasures did not please him. He loved to work than to rest. His hobbies were violin, fretwork, palmistry, sketching and painting, and photography. He was humorous and enjoyed jokes.

Nani, the lover of literature, desired to be a college lecturer. In his first attempt, he lost the post to a lady because he did not have her teaching experience. But after his M.A., he aspired for the I.C.S. Since an epidemic broke out in Delhi where the exam was to be held, his dear ones dissuaded him from filing the application. After the period for application expired, the government announced the shifting of the venue, because of the epidemic, from Delhi to Bombay (his home town)! Hence his desire for ICS was also defeated.

Noticing his amazingly clear thinking and the incredible debating power, his father repeatedly asked him to become a lawyer.Now he respected it and went for legal education. He stood First Class First in both First B.L. and Second B.L. (bagging almost all possible prizes and medals), and first in every individual paper in the examination. On one of his answer papers the examiner wrote, “Frankly, this candidate knows much more than I do.”He was not confined to the syllabus and the text book. His preparations were always exhaustive and elaborate. Extensive reading and ever-expanding knowledge are the prerequisites of a successful lawyer and Palkhivala implemented this principle in its totality. He extensively read not only tax law and constitutional law in which he was unmatched, but also several other laws on a regular basis. He mastered the fundamental laws such as jurisprudence and interpretation of statutes.

In 1944, Nani was fortunate to start practice joining the chambers of the famous lawyer Sir Jamshedji Kanga in Bombay. He had no godfathers in the profession. His rise at the Bar was meteoric. Within a couple of years of joining the profession, he was briefed in every important matter in the High Court. He was the darling of the young members of the Bar who would throng the court to listen to his arguments. He soon left his seniors way behind.

Despite his busy practice, Nani devoted time to teach law to students and was a part-time Lecturer at Government Law College, Bombay. He endeared himself to students by his clear exposition of the subjects with spices of humour and wit.

Nani Palkhivala married Nargesh in 1945. The loving and caring wife supported his mission and the achievement of his aim.

Nani fought very important cases for his countrymen in Indian courts, and for his country in international forums, most often without charging fees. The Fram Nusserwanji Balsarav.State of Bombay, Bank Nationalization case, the Privy Purse case, the Times of India case, St. Xavier’s College Society case are few among them.

The culmination of Palkhivala’s success before the Supreme Court came in the famous Fundamental Rights case (Kesavananda Bharati vs. The Sate of Kerala), which was nothing short of an all out war fought on many turfs of constitutional law. It was significant enough to call for the constitution of an unprecedented thirteen-judge bench to decide the case. It went on for five months.The courtroom and the corridors of the Supreme Court overflowed with members of the Bar and outsiders who had come from faraway places just to hear him argue. The Court held that Parliament could not, in exercise of its amending power, so amend the Constitution as to destroy or alter its basic structure.A new concept of Basic structure of the Constitution emerged in our Jurisprudence.

In 1975, “Emergency” was declared by the Government of India – the judiciary was terrorized, the press strangled, the voice of the common man muffled, and the dissenters jailed without trial.In such an atmosphere the then government tried to have the Supreme Court overrule its earlier judgment in the Kesavananda Bharati case. People feared it to be for paving the way for a totalitarian rule.But Nani was determined to fight the case and not so easily allow the nation’s onward march stayed and not so readily allow lights of freedom die. Chief Justice A.N. Ray convened a thirteen judge bench to review whether or not the basic structure doctrine restricted Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution.

On November 10 and 11, the team of civil libertarian barristers – led by Palkhivala – continuously argued against the Union government’s application for reconsideration of the Kesavananda Bharati decision. Some of the judges accepted his argument on the very first day, the others on the next. His impassioned appeal so moved all the twelve Judges on the Bench that the Chief Justice, reduced to a minority of one, had to take a step perhaps never done before or since. On the morning of November 12, Chief Justice Ray abruptly pronounced that the bench was dissolved, and the judges rose.

In all his legal battles, Palkhivala had a clear and consistent strategy. He would deeply analyze the facts, compartmentalize the legal issues and on that basis would formulate the proposition that he wanted the Court to accept. This intellectual ability with gifted and persuasive advocacy worked as magic and did wonders year after year, whether it be the Supreme Court or the High Courts or Tribunals all over India. His advocacy was extremely convincing, based on respect for the Court and devoid of any arrogance and more importantly administered firmly but with humility.

More than once, he was offered the office of the Attorney General of India, probably the youngest to get the offer.Lastly, he was pressed hard to accept it by the then Law Minister, Sri. Panampilli Govinda Menon. After a great deal of hesitation, he agreed but subsequently to satisfy the compulsion of his conscience he reversed his decision the morning of the day the announcement was to be made in Parliament.In the years immediately following, he, as the citizen’s advocate, successfully fought several historical cases against the government’s unconstitutional measures which, as the Attorney General, it would have been his duty to defend.

His experiences in life made him to believe in the existence of God. “I have deep faith in the existence of a Force that works in the affairs of men and nations. You may call it chance or accident, destiny or God, Higher Intelligence or the Immanent Principle.Each will speak in his own tongue.”

He presented India’s case in two disputes with Pakistan — first before the Special Tribunal in Geneva appointed by the U.N. to adjudicate upon Pakistan’s claim to certain territories in Kutch, and next before the International Civil Aviation Organization at Montreal and later in appeal before the World Court at the Hague when Pakistan claimed the facility of overflying India.

His oratorical talents were not confined to legal and fiscal matters only. He addressed meetings of all sorts, of medical practitioners and journalists, of corporate managers, maritime engineers and trade union functionaries, of planters and farmers, the police and the armed forces. His subjects ranged sweepingly from the spiritual to the temporal, from yoga, religion and destiny to the stock exchange and road transport. Prominent among the personalities on whom he spoke were Sri Aurobindo and Adi Sankara whose philosophies greatly inspired him.

He had many activities outside the immediate sphere of his work. He was a Trustee and Vice-President of the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. As the Chairman of Bhavan’s Governing Council of Education for over four decades, Palkhivala contributed greatly to the mould the educational policies and programmes of Bhavan which has been recognised by the Government of India as an Educational Institution of National Eminence. He served as the Chairman of Sarva Dharma Maitri Prathistan founded by Bhavan.

A number of honors came his way. To mention a handful: Padma Vibhushan; the Honorary Membership of the Academy of Political Science, New York; the First National Amity Award; the Dadabhai Naoroji Memorial Award; the Living Legend of the Law Award by the International Bar Association; a Certificate of Honour and Award by the Bar Association of India; the first Indo-American Society Award; and “Citizen of Bombay”, “Person of the Year”, “Man of the Year” and “Lifetime Achievement” Awards by various public institutions.

The man was greater than any of his achievements. Uncompromising integrity and strict discipline were the hallmarks of his character. He loved his family, his friends, his country, and humanity, as few would do.From the days he made fifteen rupees a month as a journalist to the days he made charity by millions his modesty remained the same. His innate humility, unfailing courtesy and disarming simplicity endeared him to all. The instances are innumerable.

He had been feeling immensely worried about the sharp deterioration of moral standards in the country. He appeared to have become quite distressed and even depressed at the all-pervasive corruption in our society, the hypocrisy and double standards, which according to him had become normal practice among most of the present day leaders, and particularly the manner in which the common people had become tolerant of corruption in our society.

He was against mis-governance and not good governance. He has expressed this philosophy in a very convincing manner in his inimitable style. He said: The tendency in India has been to have too much government and too little administration, too many laws and too little justice, too many public servants and too little public service, too many controls and too little welfare.

Nani was ever a great fighter. His last fight began in 1996 with himself. His seventy-six-year-old body, which had already felt the surgeon’s knife six times, was now worn out by paralytic strokes. But he worked on – in the hospital, at home, in his office, and outside. After the demise of Nargesh in 2000, he was prepared to accept the ordained. His journey of life was over at 5.15 P.M. on 11th December 2002.